DEX & CEX

Many often wonder what are the following types of crypto exchanges, therefore we have complied this brief article to highlight key differences:

- CEX (centralized exchange)

- DEX (decentralized exchange)

CEX

Centralized exchanges are marketplaces which we are all likely familiar with. A central controlling authority such as the London Stock Exchange (Equities) or Binance/Coinbase (Crypto) create infrastructure where you first are required to deposit your assets. Typically there is a KYC process which is required in order to set up an account, and once assets are deposited, you have the option to trade via a limit order or market order. The KYC requirement removes any anonymity of the user and there is also inherent exposure to counterparty risk against the exchange as the assets physically reside in the exchange account (any hacking of the exchange exposes the users to a risk of losses).

- Limit Order: This is where you specify a price which you wish to buy/sell at. The order is then added to the other limited orders placed on the exchange – these collectively form an ‘order book‘.

- Market Order: This is where you instruct to trade at the most favourable price in the order book. If you are looking to buy, you will execute at the price of the cheapest limit sell order (given that there is sufficient quantity offered at that level), vice versa.

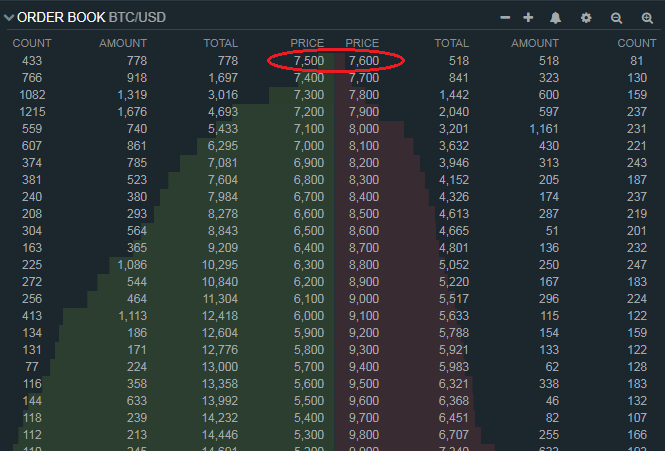

Below is an example of an order book. We can see the ‘best’ limit buy order is at a price of 7,500 (i.e. the highest price of all the limit buys). All the remaining buy order are set at lower prices compared to this order. The ‘best’ (lowest) sell limit is set at a price of 7,600. The difference between these ‘best’ prices is the ‘spread’. Note, the spread is often a sign of liquidity where larger spread indicates a more illiquid asset.

If a user was to execute a ‘market sell’ into the above order book, the price that would be traded is 7,500. Similarly a market buy would execute at a price of 7,600.

One additional point to note is the total quantity offered at limit price level. If this total was sufficiently small, a large market order would ‘walk the book‘:

- Walk the book – this term is used when there is not sufficient quantity offered at the best limit order level. Therefore a sufficiently large market order will consume all the limit offering at the best level and then move down to the second, third etc best levels, consuming all the offerings. This has the effect of moving the quoted market price.

DEX

From the above, we have learnt how standard centralized exchanges work. More importantly from centralized exchanges we learn key concepts which are required in any exchange – namely a degree of liquidity (from limit orders) which then creates a market place where price of an asset is determined by market participants, and trading is facilitates via the exchange.

Contrary to a CEX, a DEX is not centralized and acts more like a peer-to-peer market place – this is the key principal concept behind decentralized finance (defi), i.e. where middlemen and central controlling authorities are removed.

Trading is accomplished via smart contracts and as there is no central authority. You are not required to physically deposit assets to the exchange to trade, thus there is no counterparty risk (exchange hacking). Additionally there is no KYC, thus providing anonymity.

The first generation DEX’s utilized order books, similar to centralized exchanges. These order books compile a record of all open buy and sell orders for a particular asset. The spread between these prices determines the depth of the order book and the prevailing market price. On DEXs with order books, this information is often held on-chain during trades, while funds remain off-chain in your wallet.

The next and more prevalent current generation of DEX no longer utilize order books. Therefore if you do not physically deposit to the DEX (simply connect your wallet and conduct a market trade) and as there is no order book, the obvious question then is:

“where is the liquidity (limit order) which allow you to submit a market trade??”

The answer to this is based around a new concept called ‘liquidity pools‘

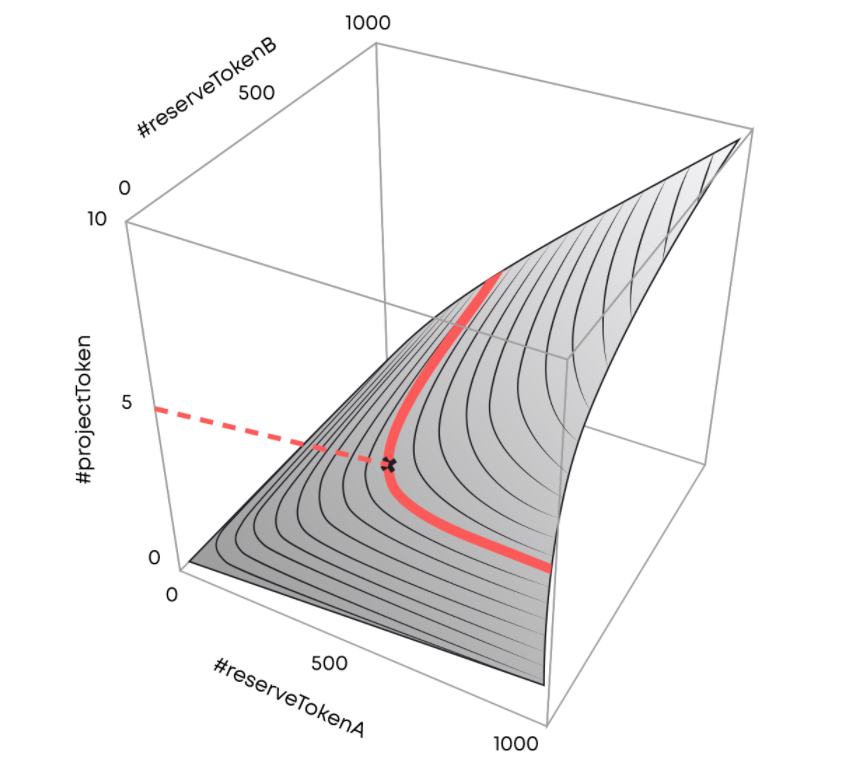

- Liquidity pool: Liquidity pools are smart contracts that hold balances of two unique tokens and enforces rules around depositing and withdrawing them. Liquidity providers will offer the DEX balances of 2 tokens (a trading pair, eg token A and token B) in exchange for the promise of a proportion of the fees generated from trading against this pair on the DEX. When a user of the DEX trades (swaps) and asset on the DEX, e.g. purchases B and sells A, the DEX will pay out asset B from the pool, and then deposit asset A into the pool. Commission from this trade will then be paid out to the liquidity providers.

For DEX’s such a Uniswap, when a token is withdrawn (bought), a proportional amount must be deposited (sold) to maintain a predefined constant. The ratio of tokens in the pool, in combination with the constant product formula, ultimately determine the price that a swap executes at. This CPMM (Constant Product Market Maker) is represented by a simple function (see below). Where X and Y are reserves of a certain (chosen) asset in the pool, and C is an unchangeable constant. The function establishes the price of a chosen token, meaning if the supply of token X increases, the supply of token Y decreases in order to maintain the constant value C.

x*y = c

If token prices change on external markets, an AMM (Automated Market Maker) doesn’t automatically adjust its prices. It requires an arbitrageur to come along and buy the underpriced asset or sell the overpriced asset until prices offered by the AMM match external markets.

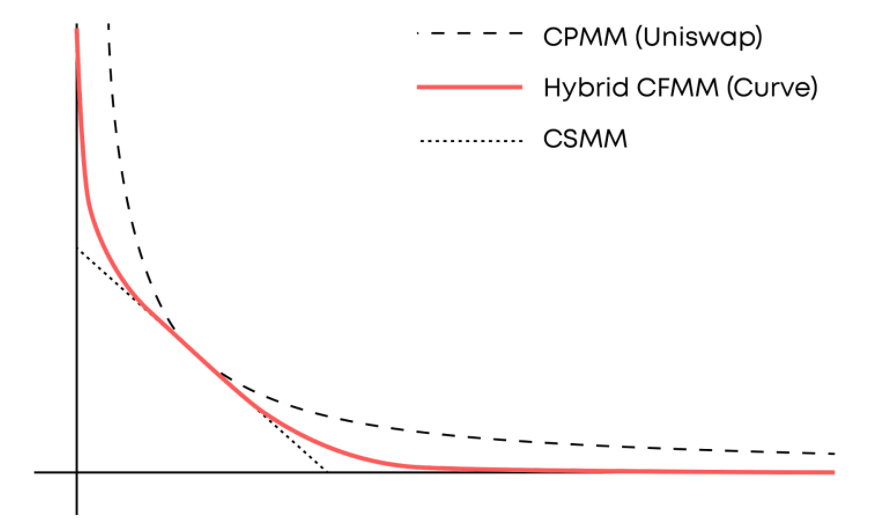

In addition to the CPMM AMM defined above, there are also other AMM’s. Some are defined below:

- Constant Sum Market Maker (CSMM): Which utilizes the following formula: x+y = c . Immediately from the equation we can see that this is a straight line chart meaning that there is no guarantee of infinite liquidity. We can compare this against CPMM in the below chart

- Constant Mean Market Maker (CMMM): This is used when addition several assets to one pool. The equation can be seen below. The AMM relies on the a average of the 3 assets being constant within the pool. These pools provide a real breakthrough because of the ability to swipe several tokens within one pool. The possibility of providing three and more assets to the pool creates a more stable and pleasant environment for traders.

(x*y*z)^(1/3) = c

We have covered the basics of DEX and some of the AMM’s on offer at presents. Lets now cover some of the risks which liquidity providers are exposed to.

Impermanent Loss

Users who provide liquidity to AMMs can see their locked tokens lose value compared to simply holding the tokens on their own (buy-and-hold strategy). Impermanent loss arises when the price of tokens inside an AMM diverge in any direction. The more divergence, the greater the impermanent loss. The term ‘impermanent’ implies that the loss is not permanent and can in fact correct itself if the ratio of the prices of the two assets return to the value when the liquidity was added. Lets look at an example of a 50/50 DAI-ETH liquidity pool to explain this phenomena:

- To partake in the pool, the LP provider must submit an equal value of both DAI and ETH to the pool

- DAI: Price=$1, Supply=10,000, Value=$10,000

- ETH: Price=$500, Supply=20, Value=$10,000

- On CEX the price of asset ETH increases $550

- Arbitrageurs now see a profit where they can buy ETH from the DEX at a cheaper price to the CEX

- If we use the CPMM (x*y=c) we can calculate how much ETH needs to be removed from the pool to increase the price to $550.

- Initially

- CPMM ==> 10,000*20=200,000 –> 200,000 representing ‘c’ which must be constant after the arbitrageurs have traded.

- ETH price of $500 was backed out by DAI/ETH, ie 10,000/20=500

- Post Arbitrageur activity

- CPMM ==> 10,488.09*19.07=200,000 –> 200,000

- ETH price ==> 10,488.09 / 19.07 = $550

- Note we have solved in order to (1) keep ‘c’ constant and (2) back out an ETH price of $550

- Initially

- If we compare pool value to buy-and-hold strategy to back out impermanent loss:

- Pool value = $20,977

- DIA: 10,488.09, $1 = $10,488.5

- ETH: 19.07 $550 = $10,488.5

- Total = 20,977

- Buy-and-hold

- DIA: 10,000, $1 = $10,000

- ETH: 20 $550 = $11,000

- Total = $21,000

- Pool value = $20,977

In the above example we can see there is a loss of $23 (this has been earned by the arbitrageur to the detriment of the liquidity provider). This is due to the better performing token being removed from the pool. Now it could be the case that trading fees might negate this and over time the pricing differential might also correct. It is therefore very important to assess the returns of an LP and the correlation of asset pair before deciding to participate as a Liquidity provider.

Summary Comparison

| CEX | DEX | |

| Advantage | -Higher liquidity -Higher transaction speeds -More advanced functionality -Easier to use -Fiat trading pairs | -Anonymity -Non-custodial -Diversity (non-reliant on CEX listing) -Trustless transactions -Lower fees -Less regulatory supervision |

Disclaimer: This article is written for the purposes of research and does not constitute financial advice or a recommendation to buy.